The way we think about history is, if not logarithmic, at least geometrical. For things in our lifetime, we process the difference between one decade and the next in a way that fades a bit (unless we’ve studied the era) a century ago (other than the World Wars, who has a strong sense of how different “average life” felt in the 1910s from the 1920s?), and then hundreds of years can get collapsed into a single mental model. You could argue that technological change justifies this: Moore’s law of computing and the equivalent advancements of the industrial age mean that things genuinely ARE shifting faster, that our world IS more different from that of the 1970s than the year 1825 was from 1775, but I’m not convinced (or at least I think we overstate the magnitude of the differences) for two reasons.

Firstly, we likely consider “significant” changes in technology to be those that we still use and that capture our attention today. The invention of the computer springs to mind easily; the proliferation of paper over vellum less so. Kerosene lighting hardly registers, since it’s been replaced, but in fact, the difference between candle light and kerosene (or between kerosene and incandescent light bulbs) is likely more profound in terms of the impact on people’s lives than that between CFLs and LEDs (excluding the environmental footprint of each).

Secondly, technology is only one part of the world in which we live. Ideas (philosophical, moral, political) and our sense of the scope of the universe may shift as rapidly and be equally or more profound. Having learned history with a U.S. focus, it’s all too easy to think of the European activity in the Americas as being fairly stagnant and not terribly significant with respect to European politics between 1492 and the 1700s, when suddenly the colonies “matter,” but that understates the rate of change, both because of the Spanish conquistadores’ theft of wealth and its impact on European geopolitics and economics, but also because over the course of 120+ years there was time for the concept of the “New World” (and its threats and opportunities) to permeate the cultures of Western Europe. By contrast, we’re not even 60 years past the moon landing yet, and have had vastly fewer people set foot on it, than had made the journey across the Atlantic by 120 years after Columbus’ voyages.

Shakespeare’s London 1613 imagines Ludovico Stuart, the Duke of Lennox, reflecting in the year 1613 on how he (and England, and London) came to be in their present circumstances. Through the year’s events and its entertainments (theatrical and chivalric), David Bergeron connects much of the prior ~30 years of English history as well as frequent Shakespearean parallels to explore the turbulence and drama of court life in Jacobean England. It’s an interesting concept, but I would have appreciated more of a strong thesis to tie the events in a more memorable way. The year 1613 was apparently a dramatic one in London, both through a proliferation of theatrical plays (including Shakespeare’s “The Tempest”), the burning of the Globe Theatre, and court events: the death of Henry (King James' son) and wedding of Elizabeth (James' daughter) to Frederick of Palatine make for an eventful read. Bergeron introduces lively and detailed descriptions of the courtly festivities, dramas, masques, and poetry, but there are lengthy summaries of plays (Shakespeare’s and others) that then get connected to the era’s political events in ways that feel a bit forced (if Much Ado About Nothing hinges on a wedding, well, Elizabeth was getting married, and if The Tempest discusses power and inheritance, James was worried about that!). Ithaca Shakespeare is performing The Tempest this summer (go see it! I helped with the physicality/”fights”!) not because it is particularly “of the moment,” but rather for the elements that are timeless.

Turn the clock back a further 412 years, and we’d find ourselves in the world of the 12th and 13th century outlined in The Welsh Princes: 1063-1283 (and rewinding from 1201 back another to 412 would put us at 789, before the start of the Viking Age). The book is challenging to read at times (there are an awful lot of Gruffuds and Llewellyns to keep straight), but well-researched and describes the evolution of Welsh nobility and its relations with the English over the 200+ year period. The Welsh were in a near-constant state of conflict during this era, both among their three kingdoms (Gwynedd, Powys, and Deheubarth), and against the English (particularly after the Norman conquest). At the same time, a few noteworthy changes occurred during the era (and that contrast with Shakespeare’s time), mostly regarding a shift from temporary, personal allegiances and arrangements to more fixed, contractual/titular modes of interaction.

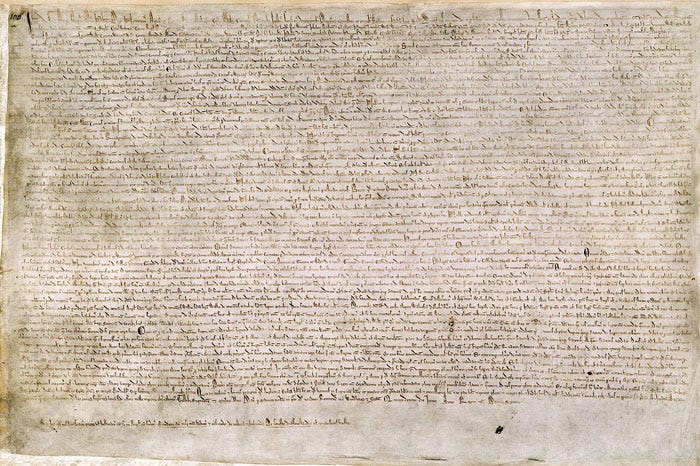

Before much castle-building (see also “Protection and Control” re: castles in Wales) warfare was focused on a) plunder (especially of livestock), and b) devastation of the other’s lands. This is the zero-sum view of the world, where princes stay princes, but one can improve one’s relative position by diminishing their wealth and resources. It can get frankly depressing to consider how much harm was done in these battles just for the sake of gaining relative status. Later, victory becomes more about controlling territory, adding the subjugated realm to one’s own. This is, in some ways, a positive development! If I’m gaining control over (and the tax revenues associated with) an area, I’d like it to be as wealthy and productive as possible, so I no longer have an incnetive to devastate it for devastation’s sake. On the other hand, it represents an end to a sort of equality, as the loser of a conflict can no longer simply pay a penalty, but must accept the leader’s authority over him. This also corresponds to an increase in written agreements: rather than simple verbal loyalty pledges (which are personal and more readily disputable), in the 1200s lords would sign written treaties with each other and with the English, binding themselves (and often their heirs) in perpetuity.

As a side note, though brutality occurs in every conflict, the Welsh experience is startling. Harold Godwinson’s 1063 campaign against the Welsh “left no one that pisseth against a wall,” and the frequency of mutilation of lords is stunning. One particularly gruesome and memorable anecdote involved a blind, castrated man who later captured his former tormentor and his son, and forced him to castrate himself or the captor would kill the boy. The prisoner, hoping to avoid this fate, pretended that he had castrated himself. His captor asked him what hurt the most. “My groin,” he said. “That’s not right. Do it for real, or your son dies.” “My heart!” “That’s not where it hurts either. I’ll throw your son off the battlements.” The third time, the prisoner did actually castrate himself, and said “It hurts in my teeth” upon which the blind man said “This time I believe you, and I know what I am talking about. Now I am avenged of the wrongs done to me, and I go happily to meet my death. You wil never beget another son, and you shall have no joy in this one.” As he said this, he hurled himself over the battlements and plunged into the abyss, taking the boy with him. In the pre-contract era, a “permanent” victory is achieved by wiping out the enemy’s line (and the potential to continue it).

While Edward I completed the conquest of Wales in 1283 (ending with the hanging, drawing, and quartering of Dafydd ap Llywellyn), the Tudors (of whom Queen Elizabeth was the last royal) were originally a Welsh family (spelled Tewdwr in Roger Turvey’s book), so maybe the Welsh had the last laugh after all.

So what do we take away from all this? Optimistically, that creation can be more lasting than destruction. As much as the loss of lives and devastation of property of the Welsh wars were tragic, 400 years later most of them were hardly remembered even on a regional scale, while Shakespeare’s plays are still with us. Secondly, that ideas and modes of interaction are not fixed, and can be more lasting than technological change. The pivot from interpersonal relationships to defined positions enabled greater centralization of control (decreasing equality, but maybe also decreasing conflict), and was likely a matter of greater significance for the modern age than, say, the invention of the trebuchet. At the same time, clearly-defined agreements can be more brittle; there’s room for me to re-evaluate what it means to be “a follower of a prince” (within limits) in a way that doesn’t exist if I commit to a very particular level of allegiance or support. If I (or my children) aren’t happy with that latter level, we have to rebel/throw out the whole arrangement.

If you know of someone who might enjoy reading this, please share:

To support Intellectual Odyssey, please subscribe: